Children can move the world

Sadako Sasaki

Sadako Sasaki

|

| Sadako Sasaki (Courtesy of Masahiro Sasaki) |

Sadako Sasaki, a Japanese girl who died of leukemia at the age of 12, ten years after the atomic bombing, has influenced many people as a result of her classmates' will to erect a monument in her memory and her determination to fold paper cranes before she died. Sympathizing with Sadako's positive attitude toward life, millions of paper cranes have been sent to Hiroshima from all over the world. And books on Sadako have given children strength and encouragement.

Ritsuko Komaki, now living in the United States, was Sadako's classmate in elementary school. She said that Sadako was a fast runner and a leader at the school athletic meets. She added that Sadako was a kind and popular girl.

After Sadako's death, Ms. Komaki and her friends launched a fundraising drive to build a memorial for Sadako and for all the children lost to war. As a result of collecting donations on the streets and from schools across Japan, the Children's Peace Monument was completed in 1958. "Handing down Sadako's story to future generations is one way to help prevent war," said Ms. Komaki.

According to the "Paper Crane Database," which the City of Hiroshima uses to keep track of the number of paper cranes offered to the Children's Peace Monument, a total of 4955 individuals and groups from 96 countries sent cranes from 2001-2007.

|

| Tomoko Watanabe (right) talks about the power of children while sharing the book "Sadako's Prayer." (Photo by Yuka Iguchi) |

A number of books about Sadako have been published. More than 20 books have been issued in Japan and more than 10 books have been published in 35 other countries.

One of these books is called "Sadako's Prayer" which was produced by ANT-Hiroshima, a non-profit organization in Hiroshima, in collaboration with an artist in Pakistan. This book has encouraged people in Pakistan to rebuild their society after a devastating earthquake in 2005 and retain their hopes for peace.

The executive director of ANT-Hiroshima, Tomoko Watanabe, 55, told us that the people of Pakistan were empowered to learn that Hiroshima residents revived their own city from the ruins of the atomic bombing. Reading the book about Sadako to Pakistani children lifted their spirits and, as the children changed, the adults regained their energy, too. Through this process of reconstruction, the "Sadako Elementary School" was established in 2008. (Daishi Kobayashi, 16, and Akane Murashige, 16)

Chisa Shibata

Chisa Shibata

|

| Chisa Shibata (right) speaks at an international event held in Kyoto in October 2008. |

Chisa Shibata, 22, a student at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, has taken part in activities aimed at abolishing landmines since she was in elementary school. She has drawn comic strips about the issue, visited countries where there are landmines to investigate actual conditions, delivered speeches, and conducted a fundraising campaign.

When she was in the 5th grade in elementary school, she saw a film about a British man named Chris Moon who lost his right arm and leg to a landmine. It was the first time she had heard of landmines and she was inspired to learn more about them. She found that landmines can maim or kill both children and adults, and the long-lasting injuries not only affect their bodies but also their minds. Chisa was shocked by what she had discovered.

Chisa felt strongly that landmines should be eliminated and so she looked for actions she might take. Before she entered the 6th grade, she drew a comic strip titled "No more landmines" which depicts the horror of landmines and how to remove them. Later, she visited Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, countries burdened by landmines, gave talks about her experiences, and called for donations to help the victims.

Asked why she engages in these activities, Chisa said, "Because I can't forget the shock I felt over the fact that children of my age out there in the world are suffering from landmines while I can enjoy playing with friends." She thinks that, lately, the awareness in Japan in regard to this problem has grown.

"Children can feel a problem in simple terms that adults will ponder as difficult," said Chisa. "That's the great power of children. But turning feeling into action is important." (Rika Shirakawa, 12)

Samantha Smith

Samantha Smith

|

| Samantha Smith (center) visited Moscow in July 1983 at the invitation of the Soviet leader Yuri Andropov. (TASS=Kyodo News) |

In 1982, when she was 10 years old, Samantha Smith, who lived in the U.S. state of Maine, wrote a letter to the leader of the former Soviet Union, Yuri Andropov. At the time, the United States and the Soviet Union were engaged in a Cold War and tensions were high due to the nuclear arsenals of both countries. Amid these circumstances, Samantha asked Mr. Andropov directly: "Are you going to vote to have a war or not?" A few months later, she received a personal reply from him.

We emailed Samantha's mother, Jane Smith, 64, who still lives in Maine, about her daughter's story.

It was on a Sunday that Jane showed Samantha a magazine article about the conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. Eyeing the photo of Mr. Andropov on the front page, Samantha asked her mother, "Why don't they ask him directly whether or not he wants to start a war?"

When Jane suggested to Samantha that she write a letter to him herself, Samantha quickly agreed.

Four months later, a reply arrived from the Soviet leader. He wrote that he didn't want to wage war and that he wished for peace. In addition, he invited her to visit the Soviet Union. As a result, Samantha took part in a youth camp in the Soviet Union and her trip was widely reported by the media of both nations.

Jane told us that Samantha's actions caused people who viewed each other with hostility to see each other as human beings, creating a deeper understanding that transcended national borders.

Sadly, Samantha Smith died at the age of 13 in a plane crash. Her dream was world peace, her mother told us. (Akane Murashige,16)

Om Prakash Gurjar

Om Prakash Gurjar

|

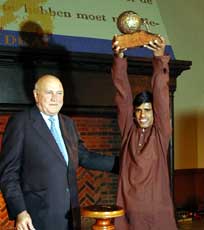

| Om Prakash Gurjar (right) at the ceremony in the Netherlands in December 2006, when he was awarded the International Children's Peace Prize. |

Om Prakash Gurjar, 16, from India, was taken from his parents at the age of 5 and forced to work on a farm. After he was rescued by an Indian NGO, he embarked on efforts for children's rights in education and in other areas of life.

After he was freed from child labor, the public school he began attending would collect money from students for their textbooks and the rent for the school building. In 2004, Om Prakash appealed for free education at public schools, collecting signatures from students and residents. About 200 children at his school joined his campaign.

The movement spread to more than 100 schools in Rajasthan state, where Om Prakash's village is located, and schools throughout that region finally became free of any cost to students.

Om Prakash is now engaged in promoting the birth registrations of newborns. He says that about 30% of babies in India aren't formally registered, and in Rajasthan state, the proportion is as high as 60%.

Om Prakash helped establish a network of 20 children's assemblies in area villages. Each assembly explains the importance of birth registration to residents. This registration helps prevent children from becoming child laborers and child soldiers. He has aided more than 500 children in obtaining birth certificates.

For these achievements, he received the International Children's Peace Prize in 2006. (Miyu Sakata,13)

Craig Kielburger

Craig Kielburger

|

| Craig Kielburger (center) takes part in a demonstration against child labor in India in December 1995. |

At the age of 12, Craig Kielburger, of Canada, established an organization to appeal for children's rights, an NGO called Free the Children. Now 26, Craig has become involved in building schools for children.

In 1995, Craig read an article about a child of the same age, a former child laborer, who was killed in Pakistan when he defied the practice of child labor. Craig was shocked to find out that there were children living in very different conditions from him. He wanted to do something for these children so he called on his classmates for help. Eleven classmates joined his cause.

They began investigating child labor through books and the internet, writing letters to government authorities, and giving presentations at local schools. At every turn, they were asked if they had actually encountered any children who suffered from child labor and they were forced to say that they hadn't.

Craig felt he needed to see the situation with his own eyes to truly understand the problem and so he succeeded in getting his parents' consent for a seven-week trip to five countries in South Asia.

After his activities were covered by the media, many other young people offered their support. Today, he has more than a million supporters in 45 nations. His organization has built over 500 schools in 16 countries, including India and Kenya. (Shiori Kosaka,13)

- Cold War

The Cold War was an international conflict primarily between the United States and the former Soviet Union, lasting from around the end of World War II to 1989. The conflict was fueled by a nuclear arms race based on the idea of containing the other side and the tension spread to involve other parts of the world, including Europe and Asia.

- Child labor

According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), child labor is considered work that prevents children under of the age of 15 from a sound upbringing. The worst forms of child labor include children under the age of 18 being forced to fight as soldiers. In the year 2004, there were about 218 million children in the world, ages 5-17, engaged in child labor.